Why the Fed Is Raising Interest Rates and What It Means

August 10, 2017

Unless you’ve spent the last eight years on Mars or asleep, you know that the biggest complaint is that the U.S. economy is sluggish:

• At an average growth rate of around 2% a year, the country’s recovery following the Great Recession of 2007-2009 has been the weakest since World War II. • The economy hasn’t grown at an annual rate of 3% in the last 12 years. • The latest GDP report showed that in the first quarter of this year, the economy grew at an annualized rate of just 1.4%, and the New York Federal Reserve Bank estimates second-quarter growth at 1.9%.

So why, then, you might ask, did the Federal Reserve Board – the country’s central bank – raise interest rates by 0.25% to 1.25% on June 14? It was the second such hike this year, and the third since the Fall of 2015. Before we answer the question, let’s take a few steps back to understand why and how the Fed changes interest rates.

By law, the Federal Reserve Board has two objectives: to maintain a stable currency by keeping inflation low, and to seek full employment. Its primary tool for accomplishing that is the target interest rate it sets for overnight loans between banks that are members of the Federal Reserve system.

The Fed defines an amount of reserve deposits every bank has to meet at the end of every day, and when a bank runs short, it’s forced to borrow money from banks that have excess reserves on hand. The rate for these loans is called the “Federal Funds Rate,” and the lending banks have incentives to charge the Fed’s target rate on these overnight loans. While the rate actually fluctuates daily around the Fed’s target, it represents a basic cost for banks. Its effect ripples through the entire financial system in terms of the rates banks charge borrowers, both businesses and consumers alike.

By making loans more expensive, the Fed slows spending, as borrowers have less cash to pay for goods and services. The resulting reduction in demand puts the brakes on the economy and inflation. The opposite is also true. When the Fed lowers rates, borrowers have more cash to spend, and if they do in fact spend it, the economy grows more quickly.

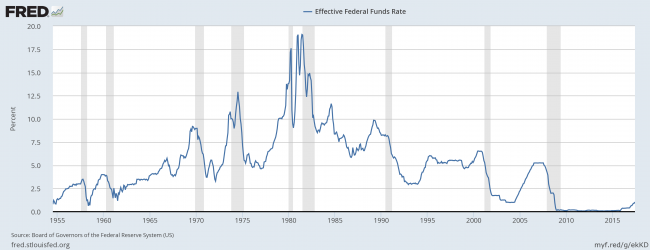

One of the by-products of rapid economic growth is inflation. When inflation gets out of control – as it did in the 1970s – the Fed raises interest rates to suppress demand. If rates get too high, they not only can cause inflation and growth to slow down but bring on a recession. The graph below shows the history of the Fed’s effective changes to the Fed Funds Rate interest rate; the grey bands highlight recessions, periods when the economy contracted. Generally, as you can see, the Fed raised the Fed Funds Rate leading up to a recession.

There have been few times when the U.S. inflation rate has hit double digits. Two of those times were in 1973-75, when it reached 11.8%, and in 1981 and 1982, then it was at 13.9% and 11.8%, respectively. As you can see in the graph, the Fed responded by raising the Federal Funds rate.

In the early 1970s, the U.S. economy was hot: it grew by more than 5% a year in 1971 and 1972, unemployment fell from 6.0% in 1971 to 4.9% by 1974, and inflation zoomed from 3.3% to 12.3% over the same period. The Fed responded raising its target Federal Funds rate six times, from a low of 3.5% in January 1971 to a high of 13.0% by July 1974, by as much as 4 percentage points at a time. The Fed’s actions precipitated a 16-month recession that resulted in a 3.2% loss in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and unemployment reaching a high of 9%. Inflation bottomed out at 4.9% in 1976.

Recovery from the 1973-75 recession was fast and furious. In 1978, the economy grew 5.6%, but in that same year prices rose 13.3%. Again, the Fed intervened, raising its Fed Funds target rate as high as 20.0% four times, in March and December 1980, and in January and May of 1981. This time there was a “double dip recession.” The first dip lasting just six months in 1980, and the second running from July 1981 to November 1982. In the first recession, unemployment peaked at 7.8% and the economy contracted by 2.2%. In the second, unemployment reached a high of 10.8%, and the economy gave up 2.7% of activity. There was pain and suffering throughout, but by 1984 inflation had been “tamed” at just 3.9%.

Today’s U.S. economy looks almost nothing like the two episodes we’ve just studied. We’re eight years out of the Great Recession, and the economy is huffing and puffing along. As of June, GDP was growing at an estimated annual rate of around 2% and inflation was about the same. To rescue and revive the economy, the Fed lowered its Fed Funds target to an all-time low of 0.25% in December 2008. That rate prevailed until late 2015 when, as we’ve noted, the Fed raised it by 0.25% to 0.50%, followed by two more equal hikes this year. But with growth and inflation feeble, we return to our opening question: why?

The answer lies in the Fed’s second objective: to maintain full employment, which economists define as between 4.0% and 5.0%. That’s the level at which business competition for labor intensifies and wages typically begin to rise, threatening higher inflation. The rate as of June was 4.4%, right in the Fed’s sweet spot. So was inflation: the Fed’s target rate for that is 2%, and that is where the inflation rate now stands. While there hasn’t been any marked increase in inflation yet, it’s generally acknowledged that it takes 18 months for Fed actions to have their intended effect, so the Fed has been acting against inflationary pressures that it believes will appear late next year.

So, both of the Fed’s goals for the economy have already been achieved. In the view of the Fed’s governors, therefore, it’s time to remove the monetary stimulus of low interest rates. In fact, Fed watchers believe the central bank will continue to raise its Fed target rate by the same, modest 0.25% bump, as many as two more times by the end of 2018.

Underlying that view is that the economy is continuing to expand, supported by the fact that the stock market has continued to advance to all-time highs. What’s more, a study published in 2015 by Stanford University economist Charles I. Jones found that the U.S. economy’s long-term growth rate, going back as far as 1870, is 2.0% – approximately where it is expected to be for this year -– and that the higher rates of growth it achieved after World War II were an aberration, not the norm.

As Forbes magazine contributor Len Sherman asked in a headline on June 2, “Can the U.S. Ever Get Back to 3% Growth?” Perhaps. That is, after all, one full point below President Trump’s stated goal. But if we get there, you can expect the Fed to have raised the Fed Funds Rate several, if not many times more.